“The gods mixed their blood with maize and cacao, and from it the first people were formed.”

Popol Vuh, The Book of Council

The first time I held a fresh cacao pod in my hands, I remember the weight of it warm, alive, faintly pulsing with the heat of the rainforest, its skin was rough and dimpled, streaked with green and gold, and when I cracked it open the air filled with a scent halfway between melon and earth after rain. Inside, the pale beans lay in their translucent pulp like pearls in a living rosary. It struck me then that this fruit had been worshipped long before it was eaten, prayed over long before it was processed. Even before I began to make chocolate, I could feel that it was, in some way, holy.

As a Christian, I’m used to thinking of food as a form of grace. Bread and wine carry meaning beyond their substance; they speak of community, of gratitude, of sacrifice. Standing with that pod in my hand, I felt the same reverence that must once have surrounded the first cacao trees of Mesoamerica, long before Europe sweetened its cup, people here believed that the gods themselves bled cacao into being, theirs was a theology of soil and rain, a faith grown straight from the forest floor.

Archaeologists tell us that traces of cacao have been found on ancient Olmec vessels dating back three thousand years. I like to imagine those first brews: dark, bitter, foaming in clay cups, poured to the spirits of maize and thunder. The Olmecs never wrote down their prayers, but the vessels tell their story the same spiral motifs that later appeared on Mayan carvings, the same serpentine curves that speak of fertility and rebirth. They understood that the forest was a conversation between gods and people, and cacao was the language they shared.

In temple art, I’ve seen depictions of noblemen sitting cross-legged before a priest who pours a stream of chocolate from one cup to another, creating a froth that symbolised breath the divine life-force. That foam was sacred. To drink it was to inhale the gods. Every cup was a prayer, every swallow a promise that the world’s sweetness and bitterness belonged together.

The Aztecs inherited and intensified this faith, they called cacao cacahuatl, and the drink they made from it xocolatl bitter water. Their emperor, Moctezuma II, was said to drink dozens of golden cups each day, believing that cacao gave him strength and clarity of mind. Yet even for him, it was not mere luxury. It was a reminder that power came from divine favour. The god Quetzalcoatl the feathered serpent had stolen the cacao tree from paradise to give it to humankind, and for that act of generosity he was cast out of heaven. Cacao was thus both a blessing and a burden, a sacred theft that required humility from those who tasted it.

I often think about that myth when I temper chocolate heat, transformation, sacrifice these words belong equally to kitchen and altar. Quetzalcoatl’s story reminds us that creation and transgression are never far apart; that sharing a divine gift always carries risk. When the Spanish arrived in the early sixteenth century, they misread the story entirely, they saw the feathered serpent on temple walls and called it demonic. Then they saw priests pouring cacao libations and mistook prayer for witchcraft, in their zeal to convert, they could not imagine that divinity might speak another language or another flavour.

The conquistadors came searching for gold, yet what they found was something subtler: a drink that shimmered with meaning. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, one of Cortés’s soldiers, wrote of seeing Moctezuma served “a great quantity of cacao in cups of pure gold.” he noted its bitterness with fascination, not pleasure to the Spaniards it tasted strange, almost medicinal but they sensed its power, they carried the beans home across the ocean, packed among silver and saints’ relics, and with them they carried the memory of a ceremony they did not yet fully understand.

In Europe, the sacred drink underwent its second baptism, sugar, cinnamon, and milk softened its bitterness; porcelain replaced clay., what had been an offering became a luxury still, traces of its holiness lingered. Monks in Spanish monasteries began to prepare chocolate for visiting dignitaries and for their own use on fasting days. The question soon arose: if chocolate nourished the body, did drinking it break the fast? It seems almost comic now, but in the seventeenth century the issue divided theologians as fiercely as any doctrinal dispute. Letters were sent to Rome; councils debated viscosity and intention. Eventually the Vatican decreed that chocolate, being liquid, did not break the fast. With that decision, the Church effectively sanctified the cup.

As demand grew, the Jesuits became the great organisers of cacao production in the New World. Their missions in South America and the Caribbean cultivated vast plantations, often relying on Indigenous and enslaved labour. Here lies one of the great contradictions of chocolate’s history: a drink born from offerings to the gods became the currency of human suffering. The same hands that raised chalices in Mass profited from the toil of those who had once considered cacao sacred. The Jesuits justified their trade by claiming they brought civilisation and salvation; they built churches with cacao wealth and sent their profits to fund schools in Europe. Perhaps they believed that the end sanctified the means, but every time I walk through a farm today, I think of the prayers whispered by those who laboured in the heat, their faith as real as that of any monk.

It is tempting to imagine a clear moral line between sacred and sinful chocolate, yet history refuses such simplicity. In Mexico, nuns in the convents of Puebla and Oaxaca developed recipes that combined local and European ingredients chilli, almonds, cinnamon, and cacao creating a cuisine that reconciled two worlds. Their most famous creation, mole poblano, still carries that syncretic spirit: spicy, bitter, sweet, complex. Legend says it was first made for a visiting archbishop, but I like to think the nuns cooked it for God. In their hands, cacao once again became an act of worship.

By the end of the seventeenth century, chocolate had conquered the Catholic world. Kings drank it for vigour, bishops for contemplation, poets for inspiration. In France, it was rumoured that Cardinal Richelieu took it as a remedy for melancholy. In Spain and Italy, apothecaries sold it as a tonic for the weak. The “food of the gods” had found a place in every stratum of society, from sacristy to salon. Yet beneath its sweetness lay the echo of the forests where it had first been revered a whisper of drums, rain, and the scent of earth after thunder.

As I read the chronicles of that era, I sense how deeply chocolate unsettled Europe’s moral compass. Was it a medicine or a vice? A comfort or a temptation? The same arguments would later be made about coffee, tea, and even tobacco, but chocolate provoked special unease because it touched pleasure so directly. To drink it was to feel briefly transported to warmth, to satisfaction, to something very like grace. The Church baptised it, but could never quite tame it.

When I melt chocolate in a bowl today, the smell rising like incense, I sometimes picture those early encounters the conquistador’s confusion, the monk’s careful stirring, the Mayan priest’s ritual pour. Each saw in cacao a mirror of his own belief: one saw power, another saw piety, another saw paradise. Perhaps all were right. Perhaps the bean has always contained every faith that has touched it, absorbing prayers like flavour notes. It is a humble seed with a divine memory.

When chocolate first reached the wider Protestant world, its reputation was already mixed: Catholic luxury to some, suspicious foreign indulgence to others. Yet even the most austere reformers could not entirely resist it. Physicians praised its restorative power, philosophers debated its moral value, and merchants saw in it an opportunity to link faith with fortune. By the dawn of the eighteenth century, chocolate had ceased to be a monastic curiosity and had become a mirror of Europe’s conscience.

As Europe industrialised, the moral tension between pleasure and production deepened. The same colonial networks that had supplied silver and sugar now delivered cocoa from the Caribbean and South America. Ships carried both beans and enslaved Africans across the Atlantic, entwining sweetness with cruelty.

In sermons of the time, preachers occasionally invoked chocolate as a symbol of moral corruption proof that the taste of Eden could still lead to exile. And yet, in the drawing rooms of London and Madrid, the drink remained a mark of refinement, served in porcelain cups painted with cherubs, the sugar stirred by hands that rarely questioned its origin.

For more than two centuries, the Church largely turned a blind eye. Its missionaries preached salvation even as its benefactors profited from plantations. The Jesuit estates of Ecuador and Venezuela thrived; Dominican friars blessed the harvest; convent kitchens perfumed the air with roasting beans. When slavery was finally abolished, the economic habits that supported it persisted under new names indenture, debt, coercion. Chocolate’s divine reputation masked its human cost.

I sometimes think that this is the moment when chocolate’s soul split in two. One half remained on the altars of comfort and ceremony, gleaming with silver and sugar. The other half lingered in the fields, among those whose labour kept the sweetness flowing. The story of redemption, once spiritual, became economic. And it was into that world that a quiet revolution of faith was about to enter.

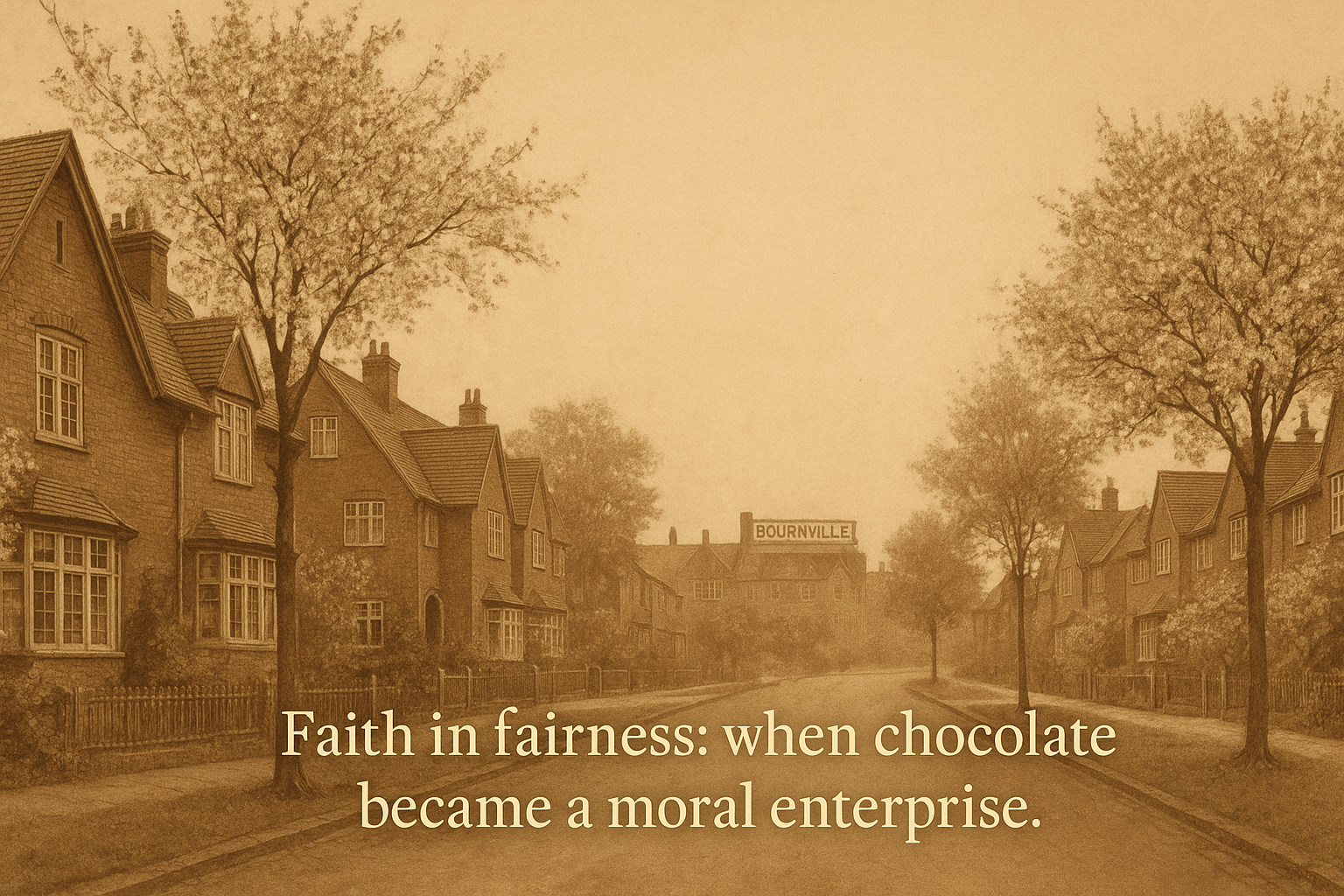

In nineteenth- century England, a small sect known as the Society of Friends better known as the Quakers began to reshape the moral landscape of industry. They were Christians who believed that the divine light dwelt in every person, that truth should be lived, not merely preached, and that business could be an expression of conscience. Because their refusal to swear oaths or bear arms excluded them from many professions, they turned to trade, banking, and manufacturing. Out of their restraint grew integrity; out of their exclusion, a new kind of enterprise.

In nineteenth- century England, a small sect known as the Society of Friends better known as the Quakers began to reshape the moral landscape of industry. They were Christians who believed that the divine light dwelt in every person, that truth should be lived, not merely preached, and that business could be an expression of conscience. Because their refusal to swear oaths or bear arms excluded them from many professions, they turned to trade, banking, and manufacturing. Out of their restraint grew integrity; out of their exclusion, a new kind of enterprise.

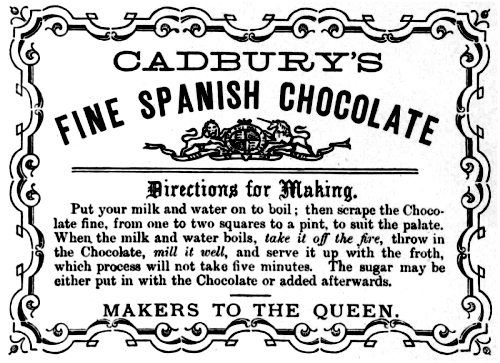

Chocolate suited them. It was wholesome, non alcoholic, and capable of offering pleasure without vice.

In an age when gin destroyed families and poverty bred despair, the Quakers proposed a gentler solace: a warm cup of cocoa instead of a bottle. They saw the factory not only as a machine for profit but as a community in miniature a place where gender equality fair wages, education, and cleanliness could demonstrate the gospel in action.

Joseph Fry in Bristol pioneered the first moulded chocolate bar in 1847. John Cadbury in Birmingham promoted cocoa as “a healthful beverage for the people.

Their influence spread far beyond their factories. They transformed chocolate from a luxury of the elite into a daily comfort of ordinary families. And they did it by weaving morality into manufacture what one might call industrial grace. When I first visited Bournville, I felt the echoes of that faith still present in the red-brick halls and tree-lined streets. Even the scent of cocoa in the air carried a hint of something more than commerce: a sense that sweetness could be an instrument of justice.

Of course, the Quakers were still products of empire. Their cocoa came from the West Indies São Tomé and West Africa, where conditions were far from the ideals they espoused. But unlike many of their contemporaries, they asked questions. Reports of forced labour on the islands of São Tomé and Príncipe in the early 1900s deeply troubled the Cadburys. They sent investigators, published findings, and eventually boycotted the plantations, moving their supply to the Gold Coast. Their response was imperfect and slow, yet it marked a turning point: faith once again challenging the system it had inherited.

By the middle of the twentieth century, the great Quaker firms had merged into corporate giants, their founders’ creeds diluted by modernity. Yet the seed of moral responsibility they planted did not die. It sprouted elsewhere in church basements, in mission fields, in the hearts of believers who saw that trade itself could be a ministry. After the Second World War, when new nations emerged across Africa and Latin America, Christian organisations began to champion the idea that fair exchange was a form of compassion. The phrase “Trade, not Aid” became a modern parable.

.jpeg) In the 1950s and 60s, church groups across Europe started importing coffee, tea, and cocoa directly from small farmers, paying them just prices and telling their stories. Out of these efforts grew the Fairtrade movement. Its founders were not economists but people of conscience priests, teachers, and volunteers who believed that the marketplace could be redeemed. They spoke of stewardship, dignity, and partnership rather than pity. Cocoa once again became a vehicle of faith, though this time the temple was the high street and the altar was the shop counter.

In the 1950s and 60s, church groups across Europe started importing coffee, tea, and cocoa directly from small farmers, paying them just prices and telling their stories. Out of these efforts grew the Fairtrade movement. Its founders were not economists but people of conscience priests, teachers, and volunteers who believed that the marketplace could be redeemed. They spoke of stewardship, dignity, and partnership rather than pity. Cocoa once again became a vehicle of faith, though this time the temple was the high street and the altar was the shop counter.

The culmination of that movement, for me, came in 1998 with the creation of Divine Chocolate, a company owned partly by the Ghanaian farmers’ cooperative Kuapa Kokoo. The very name, Divine, carried the resonance of centuries: the sacred drink, the papal blessing, the Quaker ideal, all distilled into a brand that promised fairness. When I first met members of Kuapa Kokoo years later, I saw the continuation of that long pilgrimage the sacred bean finally returned to those who nurture it. Their motto, Pa Pa Paa “Best of the Best” was both a business slogan and a prayer of affirmation.

Looking back, it is astonishing how faith has followed chocolate through every transformation. What began as ritual became commodity, what became commodity found redemption through conscience. Each epoch added its own layer of meaning, like successive coatings on a truffle: the bitter shell of exploitation, the sweet centre of compassion. And somewhere within, unchanged, lies the original divine spark the recognition that what we take from the earth must be shared with gratitude.

Sometimes, when I temper chocolate late at night, the rhythmic swirl of the spatula feels almost liturgical. The shine emerging on the surface reminds me of all those who have seen divinity in this substance: Mayan priests under a canopy of stars, Jesuit brothers in candlelight, Quaker women stirring cocoa for factory children, Ghanaian farmers lifting baskets of pods toward the sky. They would not recognise one another’s prayers, yet they are bound by the same gesture the offering of hands to something higher.

I am a Christian, and for me that gesture echoes the breaking of bread, the sharing of wine, the moment when gratitude becomes communion, but I have learned to see God’s fingerprints in many places in the myths of the Maya, in the patience of artisans, in the quiet pride of those who harvest cacao today. Faith, whatever its language, is always about relationship: between Creator and creation, between people and the work of their hands. Chocolate, in its long and tangled history, has been one of the world’s most eloquent teachers of that truth.

As this story reaches our own time, the circle feels almost complete. The same forests that once sheltered sacred trees are again being tended with reverence, though now the prayers are for sustainability rather than sacrifice. The same impulse that led monks to bless their cups now leads consumers to seek ethical labels. We are rediscovering what ancient farmers knew: that flavour begins in respect, and that every act of cultivation carries moral weight.

When I close my eyes and think of chocolate’s journey from the temples of the Yucatán to the factories of Birmingham, from colonial ships to Fairtrade stalls it feels like a pilgrimage not only through geography but through the human heart. Every civilisation that has touched cacao has projected its hopes onto it: fertility, wisdom, luxury, justice. The bean absorbs them all and offers back reflection. To taste it thoughtfully is to join that lineage of seekers who believed that goodness could be tasted, that heaven might have a flavour after all.

And so the story of faith and chocolate does not end with a final benediction but with an open invitation. The pod is cracked; the pulp is sweet; the fermentation begins. From bitterness comes complexity, from labour comes joy. It is the same mystery that all religions seek to name the transformation of the ordinary into the extraordinary, of the earthly into the divine.

As I prepare to tell the stories that follow the story of farmers, forests, and flavour I carry this history with me like a guiding aroma. The divine bean has travelled far, yet its essence remains: communion between land and life, between hands and heart. Step into the green heart of the forest, and you will find it still growing, still whispering its ancient prayer through the leaves.