Not to Belgium. Not to Switzerland.

But to the verdant, humming heart of Mesoamerica — a place older than empires, alive with the rustle of unseen life, and louder than whispered memory.

Here, long before cocoa dusted our desserts or danced in ganache, the cacao tree grew wild and revered.

Its pods weren’t just fruit.

They were treasure.

Golden and scarlet lanterns hanging from the rugged trunks — glowing with vital mystery, pulsing with sacred power. The air around them was thick with a subtle, earthy sweetness.

In this world, chocolate wasn’t a mere sweet.

It was a story. A living, breathing legend.

A Ritual in Every Sip

Long before milk, sugar, and Valentine’s Day, cacao was meticulously brewed into xocolatl — a bitter, spiced elixir, whisked to a soaring froth with rhythmic spins of wooden sticks called molinillo – (Mexican chocolate stirrer). The Maya and Mexica didn’t sweeten it; they sanctified it. Each sip was a deliberate act of reverence.

It was poured and drunk before battle, its rich aroma filling the air.

Offered to powerful gods, its frothy head seen as a sacred blessing.

Used in profound ceremonies, in quiet funerals, in vibrant fertility rites – a dark, potent thread connecting every aspect of life.

The delicate froth wasn’t just foam; it was sacred breath.

The spice — often fiery chilli, sometimes fragrant jasmine, or the grounding earthiness of maize — transformed it into an experience beyond mere taste, awakening every sense.

Xocolatl was strength. It was pure power. It was spirit given liquid form.

But how did this bitter, blessed brew leap from jungle temples to the elegant French salons, the quiet Spanish monasteries, and eventually, the bustling kitchens of Yorkshire?

To follow that extraordinary journey, we must meet a woman history has tried to silence, tried to erase.

Her name was Malintzin.

And she changed everything.

The Girl Who Listened

Malintzin was born around 1500 along the sun-drenched Gulf Coast of what is now Mexico — a child of noble Nahua lineage. Her world was vibrant, filled with the constant birdsong, the soft rustle of woven cotton, the vast green expanse of maize fields, and the lively cacophony of markets buzzing with countless languages.

She grew up hearing ancient stories whispered through generations, learning not just what to say, but when to speak and when to hold a profound silence. Her mind was exceptionally sharp, her tongue even sharper — and she possessed the rare, invaluable gift of understanding more than one language, of truly hearing beyond mere words.

But her world shifted irrevocably, tragically early.

Following the death of her father, she was sold — a mere pawn in complex local power plays.

Not for who she was.

But for what she could be traded for.

First to the Maya, where her keen ear quickly absorbed Chontal, its sounds flowing into her mind. Then again, traded once more, until her original name became just a faint whisper — one of many young girls handed over to foreigners who had come across the vast, shimmering sea in strange, towering ships, their armour glinting unnervingly in the sun.

The year was 1519.

The Spanish had arrived.

A Voice with No Map

Imagine the scene.

A group of conquistadors — sunburnt, bearded, their metal armour clanking softly, smelling of sweat and sea — receive 20 enslaved women as tribute from a Maya settlement. Most of those women were forgotten the moment their feet touched the foreign ground. Their names vanished like smoke.

But Malintzin stood out. Her eyes missed nothing.

Because she understood.

She listened with an intensity that went beyond words, grasping the subtle nuances of intent, the unspoken truths behind every utterance.

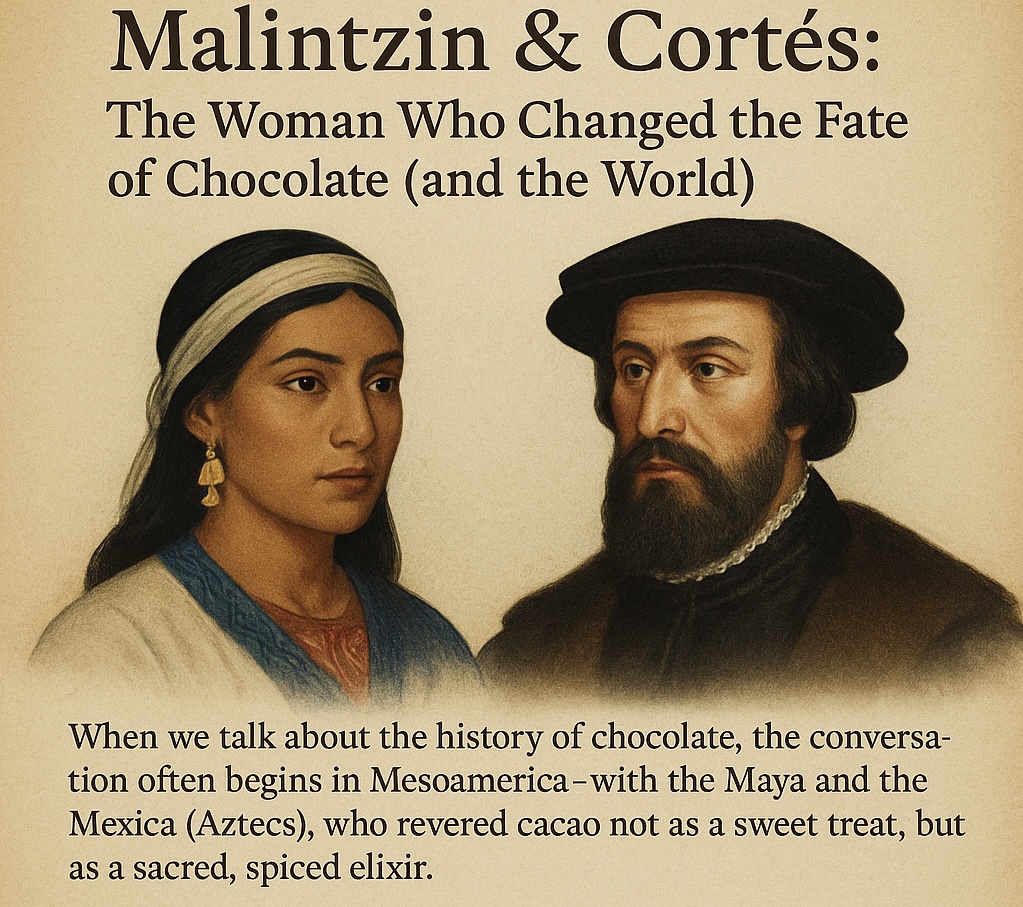

She could speak both Maya and Nahuatl, the vibrant, complex language of the Mexica (the people we often call the Aztecs). The Spanish, with their priest Gerónimo de Aguilar who spoke only Maya, suddenly realised they had found an astonishing link — a living, breathing human bridge.

Malintzin was that bridge.

And Hernán Cortés, ever the opportunist, ever hungry for power, immediately recognised her immense worth.

Not just as a simple translator, but as an indispensable diplomat.

An interpreter of intricate customs. A sharp-witted strategist. A silent, observant spy.

With her remarkable help, he could begin to navigate the bewildering patchwork of alliances and simmering rivalries that made up the magnificent city-states of Mesoamerica.

And she did it.

Not with brute violence, not with the clashing of swords, but with quiet precision. With an undeniable presence. With the sheer, transformative power of her words.

She became Doña Marina to the Spaniards.

A name that polished over her true identity, attempting to erase it, but could never truly extinguish the remarkable woman beneath.

Tenochtitlán: The City of Chocolate and Empire

At the very heart of it all lay Tenochtitlán — the Mexica capital, a breathtaking floating city of towering stone temples reaching to the heavens, fragrant gardens bursting with colour and scent, and vast, bustling markets brimming with exotic fruits, gleaming jade, brilliant feathers… and, everywhere, the rich, earthy scent of cacao.

Malintzin tirelessly led the way. Her footsteps were sure.

She was Cortés’ clear voice in the echoing palaces of powerful lords, his unerring scout across unfamiliar, treacherous terrain, his vital compass in a complex land he simply could not comprehend.

Without her sharp mind and keen insights, the Spanish would have blindly walked into fatal traps.

Without her, they may never have reached the dazzling heart of Tenochtitlán alive.

When they finally arrived, dusty and awe-struck, they were met by Emperor Montezuma II — resplendent in vibrant turquoise and the luxurious, soft pelts of jaguars. He offered them no common wine. No ordinary beer.

He offered a sacred cup.

Of xocolatl.

Intensely spiced. Lavishly foamed. Served cold, its coolness a shock against the tropical heat.

A drink of the mightiest warriors. Of the most revered gods.

Montezuma, in his grand wisdom, believed he was hosting divine visitors.

And it was Malintzin who explained it.

Not just what it was – a dark, bitter brew. But what it meant.

She detailed how it was painstakingly prepared, the sounds of grinding beans and whisking sticks now in their minds.

How it was solemnly consumed.

What it symbolised – power, reverence, divinity itself.

She was the profound reason they didn’t recoil from its initial, startling bitterness, but instead marvelled at its complex richness.

She was the reason they took this strange, dark drink seriously, understanding its profound significance.

And so, with Malintzin's translation, chocolate, truly understood, began its fateful journey across the sea.

Beyond Malintzin: Other Forgotten Women of Cocoa

Malintzin’s story is a powerful reminder that history often overlooks the women whose influence was subtle yet profound. She is not alone. As chocolate began its journey across oceans and empires, other remarkable women played crucial, often unacknowledged, roles.

Consider D. Maria Correia, known as "The Black Princess." Born in Príncipe in 1788, she was a woman of immense wealth, power, and enterprise. Her father was a wealthy Brazilian farmer, and her mother a native of Príncipe, an island that would become famous as one of the "Chocolate Islands." D. Maria's first husband, José Ferreira Gomes, is believed to have planted the very first cacao tree in São Tomé and Príncipe. While the land she received as a wedding gift was earmarked for cocoa cultivation, she chose to build a magnificent church there instead, a testament to her independent spirit and vision.

Consider D. Maria Correia, known as "The Black Princess." Born in Príncipe in 1788, she was a woman of immense wealth, power, and enterprise. Her father was a wealthy Brazilian farmer, and her mother a native of Príncipe, an island that would become famous as one of the "Chocolate Islands." D. Maria's first husband, José Ferreira Gomes, is believed to have planted the very first cacao tree in São Tomé and Príncipe. While the land she received as a wedding gift was earmarked for cocoa cultivation, she chose to build a magnificent church there instead, a testament to her independent spirit and vision.

Despite her significant influence – owning two palaces and becoming the largest donor to yellow fever victims in Lisbon in 1858 – her story was later distorted. Colonial scribes, through racist and sexist prejudices, painted her as a "depraved nymphomaniac" and "man-eater." After her death in 1861, her vast estate was unjustly claimed by her husband's godson, and she was left without an epitaph or even a grave stone. D. Maria Correia, like Malintzin, was a woman of immense power whose true impact was deliberately obscured, her legacy silenced by the biases of her time. Yet, her connection to the very origins of cocoa cultivation in the "Chocolate Islands" means her presence, like a whisper in the wind, is an undeniable part of chocolate's global story.

Empire in a Cup

The Spanish, accustomed to sweetness, adapted it.

They added fragrant cinnamon. Precious sugar. Rich, creamy milk.

But the bones of the drink — the profound essence of the cacao — remained, a dark, potent heart.

Soon, its intoxicating aroma was being savoured in hushed Spanish monasteries, poured into delicate porcelain in the opulent courts of Versailles, celebrated in the elegant, chattering Georgian parlours. It trickled from the aristocracy, slowly, inexorably, into the everyday lives of ordinary people.

Cacao had become chocolate. A global sensation.

But it had also become currency, conquest, commerce – a symbol of a world transformed.

And in the shadows of this immense explosion, this vast global shift, stood women — the girls who had once been passed between hands like mere coins, the princesses whose legacies were twisted, now shaping the very course of empires with nothing but their incredible understanding, their resilience, or their sheer presence.

Malintzin bore Cortés a son, Martín — often referred to as the first mestizo, the first symbolic child of coloniser and colonised, a living testament to the collision of worlds.

These women were utterly, profoundly part of everything — and yet, tragically, often claimed by no one, or worse, vilified.

Traitor? Survivor? Translator of Worlds.

For centuries, Malintzin was fiercely vilified. Her name became a curse.

In Mexican Spanish, “malinchista” became a potent, bitter word for traitor. For someone who sides with foreigners, who betrays their own.

But what true choice did she truly have, a young woman caught in the crushing gears of history?

She didn’t ask for empire.

She didn’t draw the sword that bled the land.

She simply stood in the terrifying middle of an unstoppable storm — and she spoke. She translated survival.

She used the only power she possessed: her piercing insight, her formidable intelligence, her clear, unwavering voice.

And with it, she changed the world.

A Final Sip

So next time you hold a piece of chocolate to your lips — especially if it’s dark, complex, and a little bitter — pause.

Close your eyes. Feel its smooth texture, let its rich scent fill your senses.

Think not of the sleek shops of Belgium or the snowy peaks of Switzerland.

Think of verdant jungles, alive with unseen sounds. Of gleaming gold goblets and the rough feel of stone temples. Of the rhythmic thump of wooden drums.

Think of a remarkable woman who understood the immense weight of words, and the profound meaning behind a bitter sip.

Think of D. Maria Correia, the powerful princess whose story was almost erased.

Think of Malintzin.

The girl who translated a kingdom.

The woman who ensured the first taste of chocolate in Europe wasn't mocked as strange — but remembered as a revelation.

These forgotten women may not have wielded swords,

But they changed the fate of chocolate —

And the world, forever.